In World Economy News 07/11/2016

Here’s a broad picture of how households have fared over the past three-plus years of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s economic program, which was meant to reflate Japan’s economy, leaning heavily on the Bank of Japan’s extraordinary asset-buying.

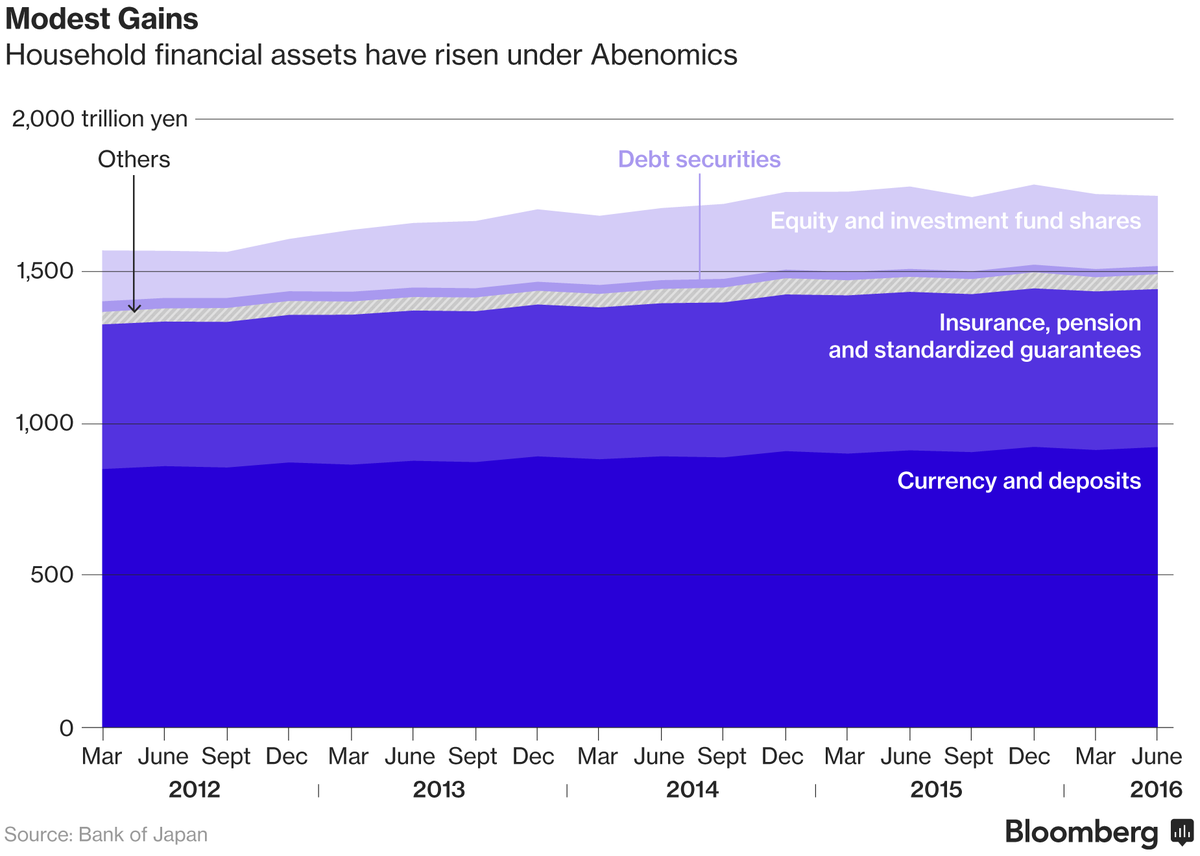

The stock market soared after the BOJ’s bond-buying program helped weaken the yen, providing a boost to Japanese exporters. The value of households’ equity holdings rose in the process, but renewed strength in the currency this year has stalled the trend. There is growing pessimism about the prospects for a sustainable recovery in Japan, which has weighed on stocks.

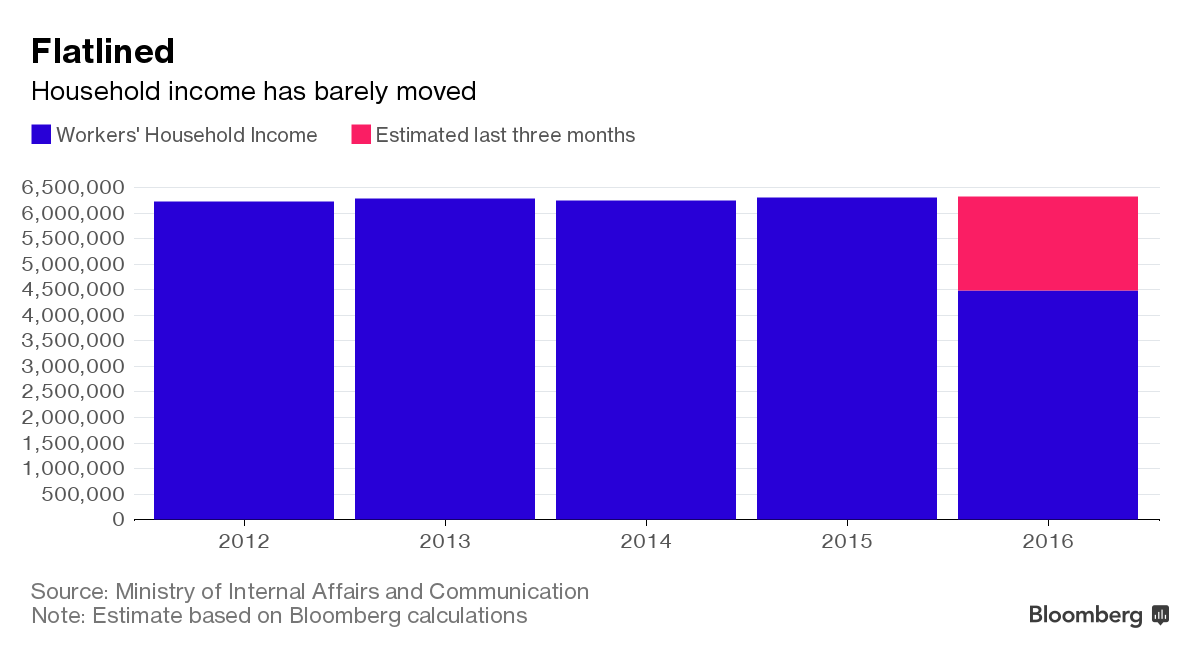

One of the knocks against Abenomics has been that it mostly benefited big businesses and more affluent households — fewer than a third of Japanese households own stocks. While share prices are higher, wages have barely moved and household income has stalled. This has frustrated policy makers who want to see rising pay provide workers with more purchasing power.

One-person households, which now account for more than 30 percent of the total, haven’t fared well. About 48 percent had no financial assets in 2015, the highest level since 2007 and up from 39 percent in 2014, according to a BOJ survey.

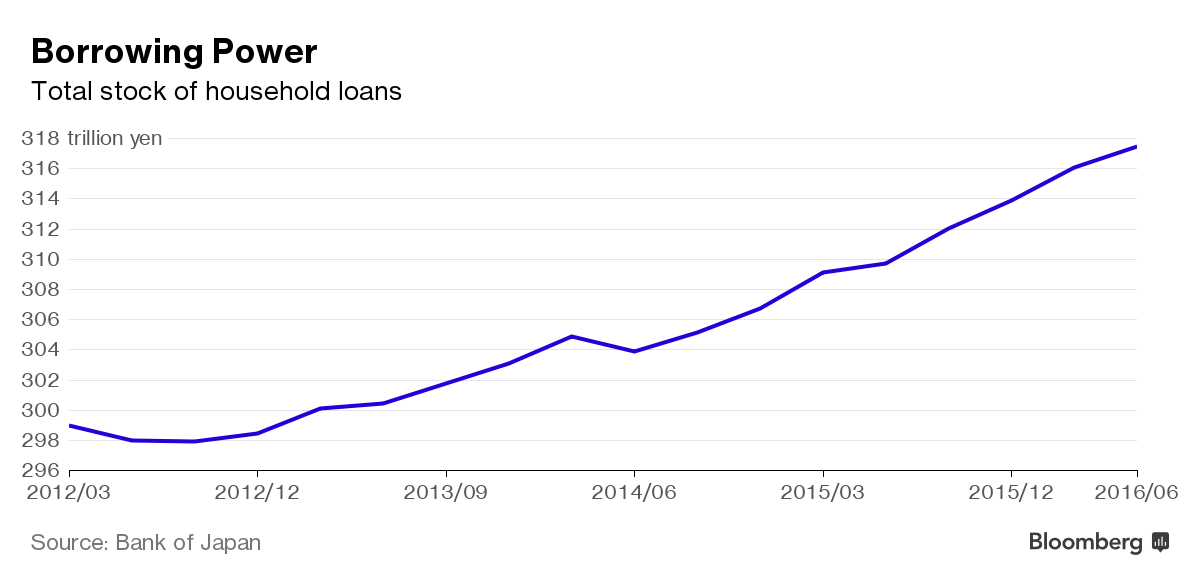

With incomes flat and interest rates at rock-bottom levels, it’s no surprise that borrowing has increased. The value of outstanding mortgage loans from private banks has increased almost 8 percent between 2012 and 2016.

In an aging nation increasingly dependent on pensions and fixed income, more than half of people think interest rates are too low, according to BOJ surveys. The number of people who thought rates were too low shot up to 65 percent after the BOJ introduced negative rates early this year.

A premise of Abenomics was that higher corporate profits would lead to wage increases and more private consumption, fueling investment. But with the higher pay never materializing, consumption has remained weak, growing by more than 1 percent in a quarter only once over the past three-plus years. And that was in the first quarter of 2014 as shoppers rushed to stores before a sales-tax increase took effect in April that year, causing consumption to tumble 4.8 percent the following quarter.

Source: Bloomberg